Shaping the future by hearing the past

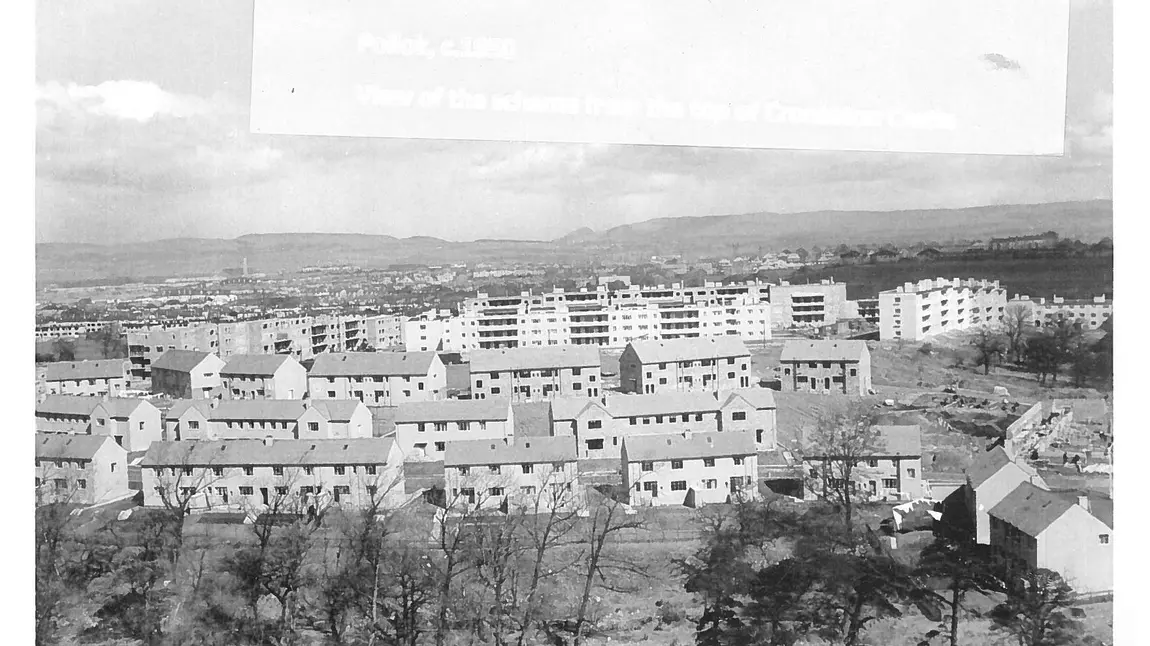

Pollok is complicated, more complicated than you might think. People will tell you that there’s old Pollok, there’s new Pollok and some bits that aren’t even Pollok at all.

Unearthing stories

Unearthing stories about a place is always more nuanced than you ever imagine. For people who have lived somewhere all their lives, breathed it in and speak about it with a love that you would for a close friend, you’ll discover that not everything meets the eye.

[quote]“We have been capturing the stories from the young and not so young to create a picture of a place.”[/quote]

The HLF-supported Pollok 80/20 project has proved to be such a project. We, The Village Storytelling Centre, are searching high and low to discover the stories of 80 years of Pollok social housing. We are trying to turn these stories into an interactive map that generations of people can come and listen to and enjoy the fabulous, hidden oral history that exists in a much-maligned and misunderstood area of Glasgow. We hope this project brings people from across the city to hear the sordid behaviour of one particular park bench, hear the voices of people who can tell you what it used to be like and how they feel about it now.

We have been capturing the stories from the young and not so young to create a picture of a place. A picture that goes beyond the assumptions people make of an area.

Preserving voices

We’ve heard the sound of laughter emanating from one house on the corner of the street. The sounds of the old shopping centre and the trams that would pass by regularly have filled our ear. For a moment the past has been in the present and the present has occupied the past.

[quote]“We are in a privileged position to go and collect the stories of the people who live in this area and hear the rich knowledge that resides in every house, in every community hub, in every shop.”[/quote]

We are still at an early phase of our project and we are only just discovering the complexity and meaning that this area has to the people who occupy it. From those who can tell you about the church that was moved brick by brick from a different part of the city to the shenanigans that would occur up at Crookston Castle, we’ve learnt that not every story has to be epic or huge, it’s the small moments of intimacy that you experience when discovering someone’s life history. The impact and imprint that they have made on the lives of people around them even if they don’t see it as such. We are in a privileged position to go and collect the stories of the people who live in this area and hear the rich knowledge that resides in every house, in every community hub, in every shop.

It is with thanks to HLF that the voices of people can be heard for years to come, creating art out of the everyday.

Pollok may be old, or it may be young. But for the people who know it, what matters is that it’s here and it has thousands of voices that can shape and share its future by bringing up its past.

Find out more about HLF's Stories, Stones & Bones celebrations on the HLF Stories Tumblr.

You might also be interested in...