Tracing the impact of the Somme on rural communities

With nearly 60,000 killed and wounded, 1 July 1916 - the opening day of the Battle of the Somme - was the bloodiest day in British military history.

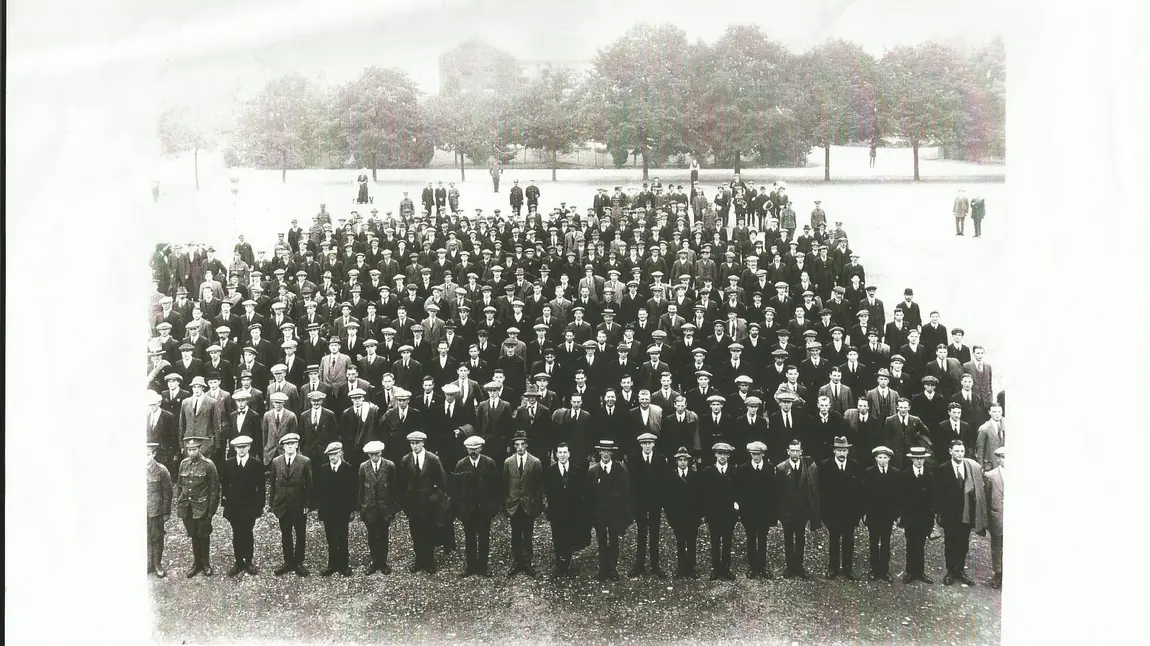

Among the casualties were thousands of 'Kitchener’ volunteers, who had joined locally raised battalions in 1914 and 1915, trained in Britain and then held quiet sections of the Western Front. Their units are often known as ‘Pals Battalions’ and are traditionally associated with industrial towns. Yet rural areas also enthusiastically raised local battalions which suffered equally.

[quote= Volunteer soldier, Bill Curtis]"I joined up before I was 18 really, but I told them I was 18, that was near enough them days." [/quote]

Typical of the youngsters who joined up in rural areas was Bill Curtis of Salhouse in the Norfolk Broads: "They said Kaiser Bill was coming over with his men," he later recalled. "All the youngsters went ... I joined up before I was 18 really, but I told them I was 18, that was near enough them days."

Men walked enormous distances to enlist at the barracks of county regiments. Chronically low wages in the countryside were a spur - George Howell of Walsingham, Norfolk, claimed: "I went into the Forces – like a fool! I was, I was a young fool. The reason why I joined was to get my feet from under the table ... There was four or five to be fed."

For many young farmworkers, it was the first time they had eaten three meals a day without back-breaking work: "We were damn glad to get off the farms." One report suggested that many recruits put on two stone during training.

Disaster

However, the five month-long Battle of the Somme was a disaster for these rural battalions. Devastated units simply ceased to exist and could not be reconstituted in the same way because there were no local reinforcements.

On 1 July 1916, 11th Suffolks – the Cambridgeshire battalion – suffered 527 casualties. Two of my father’s uncles serving in it were wounded that morning. Obadiah Perrin’s wounds were patched up and he was drafted into the 6th Berkshires, another rural Kitchener battalion, although from a county he had never visited. They were flung into battle again in late September and Obie was killed. Obie’s brother Lawrence was later wounded but survived the war.

The worst catastrophe overtook the three Norfolk Kitchener battalions. On the opening morning of the Somme, the 8th lost 489 men, and in the follow-up attacks, the 9th lost 448, and the 7th 105. The 7th went on to lose a further 662 men in the course of the next week’s fighting and the 9th 239 men later in the battle.

A generation of farmworkers was affected by a sense of loss and betrayal; George Howell said: "It was an education to me which I shouldn’t have got. The futility of it all."

Censorship

News of the disasters was heavily censored. While in Norfolk early newspaper reports spoke of a "Great Battle", no casualty lists appeared until early August and these used misleading phrases such as: "the following are reported on various dates" until the end of October. In Shropshire, the casualty numbers started appearing from 21 July, but sparse information was overshadowed by propaganda.

In Cambridgeshire, 14 officer losses of the 11th Suffolks were reported as early as 14 July, but with only five names of rank and file casualties. As late as 11 August, the press noted: "Details of losses in the great charge of the Suffolks on the historic 1 July are still being received" – a cynical decision by censors, considering the slaughter occurred in the first half hour of the attack.

With rural battalions drawing men from villages all over the counties, there was little parallel with what was experienced by the families of the urban Pals Battalions, where the whole community could mourn. Instead, families coped with loss in ignorance and isolation.

[Editor's note: Quotes are from interviews made in the early 1980s; for more details see Nick Mansfield’s book English Farmworkers and Local Patriotism, 1900-1930 (Ashgate, 2001).]

Do you have a project in mind?

If you have an idea for a project exploring how the Battle of the Somme affected your local community, visit our First World War: Then and Now grants page.